After Crater Lake, only 33 miles in circumference, was circumnavigated, we crossed the Pumice Desert (a patch of treeless scratch less than a half-mile across) and flew north toward the belly of Oregon. Long, rolling rise-and-falls, seer-suckered by sagebrush, scruff and cattle, persevered on US 97 until we took the small road at Madras, drawn eastward by a tiny brown square on our AAA map labeled Clarno Unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. We had purchased a Golden Eagle year-long National Parks pass at Lassen, and we were committed to using it.

After Crater Lake, only 33 miles in circumference, was circumnavigated, we crossed the Pumice Desert (a patch of treeless scratch less than a half-mile across) and flew north toward the belly of Oregon. Long, rolling rise-and-falls, seer-suckered by sagebrush, scruff and cattle, persevered on US 97 until we took the small road at Madras, drawn eastward by a tiny brown square on our AAA map labeled Clarno Unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. We had purchased a Golden Eagle year-long National Parks pass at Lassen, and we were committed to using it.

.

After the intermittent, insignificant traffic on US 97, we saw cars on Oregon’s Route 218 numbered fewer than the miles we drove. Here the land sat on edge, layers of rock lifted and bent vertical by geologic cramps. Here man-in-the-land is defined by water. Creeks enable ranches; else all is desolate. Ann expressed wonder that we had chosen this road. It was a hypotenuse on paper, a road way less traveled. In short, an adventure into the interior of both Oregon and ourselves. Each twist of the pavement brought new, but nearly similar landscapes, and each landscape demanded that we examine it. Here there was no covey of tourists’ eyes claiming every sight. Whatever was there was there, was there for us alone. And it was our responsibility to see it.

After the intermittent, insignificant traffic on US 97, we saw cars on Oregon’s Route 218 numbered fewer than the miles we drove. Here the land sat on edge, layers of rock lifted and bent vertical by geologic cramps. Here man-in-the-land is defined by water. Creeks enable ranches; else all is desolate. Ann expressed wonder that we had chosen this road. It was a hypotenuse on paper, a road way less traveled. In short, an adventure into the interior of both Oregon and ourselves. Each twist of the pavement brought new, but nearly similar landscapes, and each landscape demanded that we examine it. Here there was no covey of tourists’ eyes claiming every sight. Whatever was there was there, was there for us alone. And it was our responsibility to see it.

We  saw a prairie chicken, many hawks, rock taluses of every hue from red to red and from gray to green, and one man with horse and sheep dog. After the shallows named the John Day River, we parked at Clarno and walked back through 44 millions years on the quarter-mile self-guided tour through the rocks under a tall palisade of rock spires. Here were the frozen remnants of massive mud slides called lahars that trapped and siliconized leaves and branches from what was once a tropical rain forest. Every broken boulder held fossils trapped; the guide pamphlet hailed Clarno as a treasure unique in the world. It was 4 p.m., bakingly hot, and at the clipboard guest book hidden under the only sign at the Monument, we signed in below the Komura family of Nagoya, Japan, as only the fifth car to visit this day.

saw a prairie chicken, many hawks, rock taluses of every hue from red to red and from gray to green, and one man with horse and sheep dog. After the shallows named the John Day River, we parked at Clarno and walked back through 44 millions years on the quarter-mile self-guided tour through the rocks under a tall palisade of rock spires. Here were the frozen remnants of massive mud slides called lahars that trapped and siliconized leaves and branches from what was once a tropical rain forest. Every broken boulder held fossils trapped; the guide pamphlet hailed Clarno as a treasure unique in the world. It was 4 p.m., bakingly hot, and at the clipboard guest book hidden under the only sign at the Monument, we signed in below the Komura family of Nagoya, Japan, as only the fifth car to visit this day.

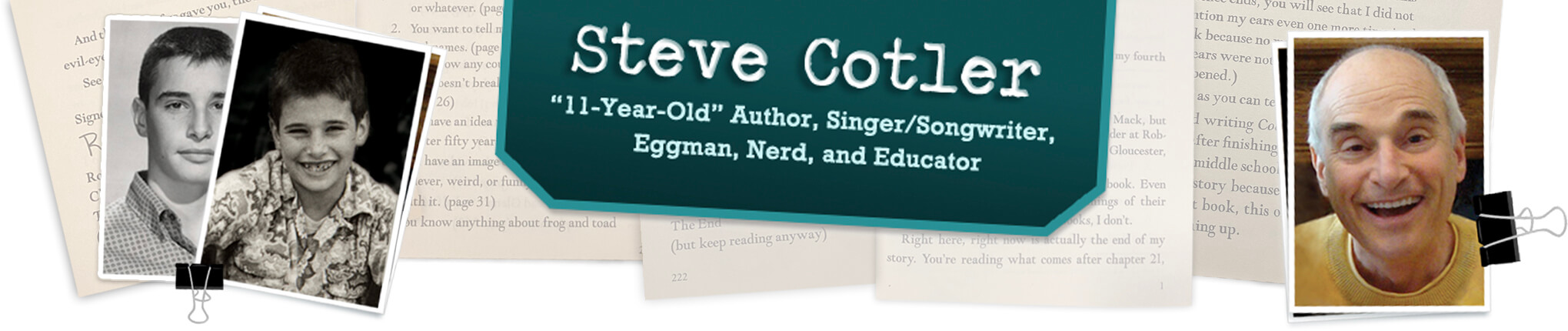

![FOSSILM[1]](http://stevecotler.com/tales/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/FOSSILM1-162x300.jpg) Between Clarno and the Columbia River to the north, just 20 miles away, lay the seat of Wheeler County, aptly named Fossil, population 430. The following sign told us that unless we turned left, we would bypass the “City Center”, so we detoured through a well-tended, attractive hamlet far enough from everywhere. Main attraction: a fossil bed directly behind the high school that invited visitors to dig for their own treasures. No fee buffet, but only take what you can eat. We passed, having already done our fossilizing at Clarno. The town looked larger than its written population, an opinion confirmed by a mannish woman smoking outside the Town Office, who upped the statistic to 550.

Between Clarno and the Columbia River to the north, just 20 miles away, lay the seat of Wheeler County, aptly named Fossil, population 430. The following sign told us that unless we turned left, we would bypass the “City Center”, so we detoured through a well-tended, attractive hamlet far enough from everywhere. Main attraction: a fossil bed directly behind the high school that invited visitors to dig for their own treasures. No fee buffet, but only take what you can eat. We passed, having already done our fossilizing at Clarno. The town looked larger than its written population, an opinion confirmed by a mannish woman smoking outside the Town Office, who upped the statistic to 550.  Then, struck unilateral by a Great Idea, I spun a U on the main street, babbling aloud about oncoming traffic (none) and the possibility that my maneuver was illegal (probably), and parked at the Fossil Mercantile, the largest (only) store in town. I would purchase a postcard naming the town, send it to my friend Tom, co-founder of the Fossil Company in Dallas, and invite him to send an advertising team here to dig for fossils and create a paleontological campaign for his watches.

Then, struck unilateral by a Great Idea, I spun a U on the main street, babbling aloud about oncoming traffic (none) and the possibility that my maneuver was illegal (probably), and parked at the Fossil Mercantile, the largest (only) store in town. I would purchase a postcard naming the town, send it to my friend Tom, co-founder of the Fossil Company in Dallas, and invite him to send an advertising team here to dig for fossils and create a paleontological campaign for his watches.

Like the town, the store was larger and more interesting than expected. It housed three customers, all locals. In addition to bananas and belts, hanging from every rafter were quilts handmade by Fossil matrons, visible testimony to the recent Wheeler County Centennial, and now on sale to benefit the Fossil Museum fund. Rarely have I been so impulsive. In a fit of spendiferous wind, I accost Charlene, a young woman inventorying yard goods, and force her to sell me two: one for my youngest daughter and one I don’t know why.

As my credit card company fights with their own computers over a pending one dollar charge unresolved at our last gas up station, I learn that Charlene is a native, youngest of five children, and “an old maid.”

As my credit card company fights with their own computers over a pending one dollar charge unresolved at our last gas up station, I learn that Charlene is a native, youngest of five children, and “an old maid.”

“There’s not much to do here if you don’t drink,” Charlene tells us without a trace of self-pity. “I did leave after high school…and got a good job with Jensen Newfield, commercial fishing, up there in Mt. Hood. And they even sent me to a couple of classes, but I guess I just like small towns.” She is attractive in an uncomplicated way.

What supports Fossil, I ask.

“Agriculture, mostly.” She looks right at me as I speak. “And tourists, some. And we’ve got retired folks. When the sawmill closed, up there at Kinzua, it was tough for a while, but it’s, I guess, okay now.”

Later, Ann comments that Charlene could be the salvation some good ol’ boy’s life. And I wonder aloud if any of those lads will be wise enough to trip over her.

The back of the van puffed up with garbage bags of quilts, we head north to the Columbia and cross into Washington.