Much of the talk about unsettled times ahead looks to oil as a cause: economies will undergo transition and regional conflicts will increase.

Much of the talk about unsettled times ahead looks to oil as a cause: economies will undergo transition and regional conflicts will increase.

Lake Chad is an exemplar. At one time the world’s sixth largest lake, included in four African countries (Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria), it has, in less than a half-century, shrunk to one-tenth its former size. Fed almost entirely by the Chari River, Lake Chad has no outlets and is very shallow, averaging only a few meters deep; a decrease in water volume greatly shrinks the perimeter. There are former lakefront villages that are now 100 km from the shore.

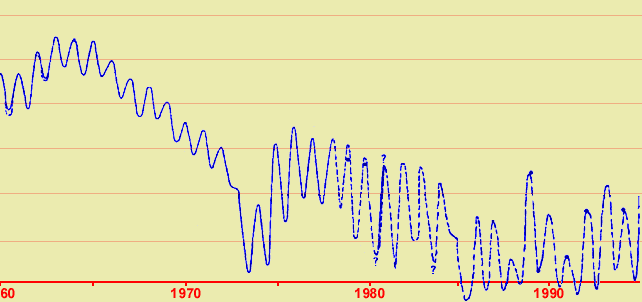

There are several reasons for the drying up of Lake Chad. Most important is decreased rainfall, but greatly increased irrigation and the damming of rivers for hydroelectric power, which accounted for only a sixth of the 1963-75 decrease (see graph below) as reported in a 2001 paper by University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers Michael T. Coe and Jonathan A. Foley, is becoming more important because of population increases and the resultant competition for the limited water resources.

This water shortage, like all shortages, has engendered controversy over which countries have rights to the remaining water. On a smaller scale, farmers and herders tangle with fishermen: water diversion for crops and livestock vs. keeping levels high to improve declining fish population. Look for these conflicts to intensify.

With the exception of Nigeria, which has great oil wealth, the other Lake Chad countries are poor. Conflicts among them are likely to stay local. But imagine what disagreements may arise in the future over water from rivers that separate wealthy, militarily strong nations.

* * * * *

Chad, the country, is named after its lake. The word “chad” in a local language means “large expanse of water.” Lake Chad actually means “lake lake.”