Drive north in the belly of Oregon through long, rolling rise-and-falls, seer-suckered by sagebrush, past scruff and cattle, persevering on US 97 until you find a road at Madras that leads eastward toward a tiny brown square on your AAA map labeled Clarno Unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. After the intermittent, insignificant traffic on US 97, you’ll find cars on Oregon’s Route 218 numbering fewer than the miles you drive.

Drive north in the belly of Oregon through long, rolling rise-and-falls, seer-suckered by sagebrush, past scruff and cattle, persevering on US 97 until you find a road at Madras that leads eastward toward a tiny brown square on your AAA map labeled Clarno Unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. After the intermittent, insignificant traffic on US 97, you’ll find cars on Oregon’s Route 218 numbering fewer than the miles you drive.

Here the land sits on edge, layers of rock lifted and bent nearly vertical by geologic cramps. Here man-on-the-land is defined by water.  Creeks enable ranches; else all is desolate. Oregon 218 is wanderer’s hypotenuse; a road much less traveled.

Creeks enable ranches; else all is desolate. Oregon 218 is wanderer’s hypotenuse; a road much less traveled.

We drove it and found an adventure into the interior of both Oregon and ourselves. Each twist of the pavement brought new, but nearly similar landscapes, and each landscape demanded that we examine it.

We saw a sage grouse, many hawks, rock taluses of every hue from red to redder and from gray to green, and one horse with man and sheep dog. After the John Day River shallows, we parked at Clarno and walked back through 44 million years on the quarter-mile self-guided tour under a tall palisade of rock spires. Here were the frozen remnants of massive mud slides (lahars) that trapped and

We saw a sage grouse, many hawks, rock taluses of every hue from red to redder and from gray to green, and one horse with man and sheep dog. After the John Day River shallows, we parked at Clarno and walked back through 44 million years on the quarter-mile self-guided tour under a tall palisade of rock spires. Here were the frozen remnants of massive mud slides (lahars) that trapped and  siliconized leaves and branches from what was once a tropical rainforest. Every broken boulder held fossils; the guide pamphlet hailed Clarno as a treasure unique in the world.

siliconized leaves and branches from what was once a tropical rainforest. Every broken boulder held fossils; the guide pamphlet hailed Clarno as a treasure unique in the world.

It was 4 p.m., bakingly hot, and at the clipboard guest book hidden under the only sign at the Monument, we signed in below the Komura family of Nagoya, Japan, as only the fifth car to visit this day.

It was 4 p.m., bakingly hot, and at the clipboard guest book hidden under the only sign at the Monument, we signed in below the Komura family of Nagoya, Japan, as only the fifth car to visit this day.

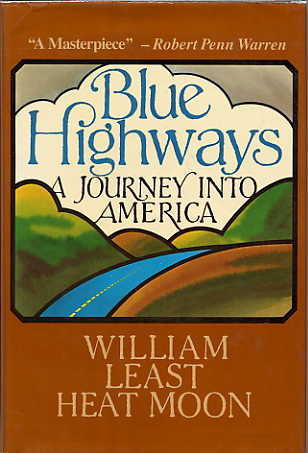

Oregon 218, the kind of road William Least Heat-Moon called a “blue highway,” had no covey of tourists’ eyes claiming every sight. Whatever was there, was there for us alone.

It was our responsibility to see it.