It was the wrong season for whales. It was the wrong month for sea lions. The gulls only tolerated me and to be true, I enjoyed them only within my limited fascination for the inexplicable red spot on their yellow beaks. For the first 20 minutes, a lone brown pelican held my attention as it repeatedly wheeled over and anchovied point-first into a school unaware of summer vacation.

It was the wrong season for whales. It was the wrong month for sea lions. The gulls only tolerated me and to be true, I enjoyed them only within my limited fascination for the inexplicable red spot on their yellow beaks. For the first 20 minutes, a lone brown pelican held my attention as it repeatedly wheeled over and anchovied point-first into a school unaware of summer vacation.

I was cabin cruising Pacifically with a friend. A pleasant sun, some wind, and water that peaked and curled like  icing on a cakemaker’s masterpiece. Then the first symptoms appeared. Laughing into my Dos Equis, I guessed out loud that too much clean air could make a man dizzy, his knees a bit watery. I sat down and stared at the horizon, limply watching headache and nausea bobbing grimly across the deep, smelling my fear. Irrevocably, I released my beer and flopped down onto a deck cushion accustomed to human instability. I looked to my friend for help. He smiled wanly and ruddered right, turning the sun out of my face. He has a kind heart, but there was nothing else for him to do. I was seasick.

icing on a cakemaker’s masterpiece. Then the first symptoms appeared. Laughing into my Dos Equis, I guessed out loud that too much clean air could make a man dizzy, his knees a bit watery. I sat down and stared at the horizon, limply watching headache and nausea bobbing grimly across the deep, smelling my fear. Irrevocably, I released my beer and flopped down onto a deck cushion accustomed to human instability. I looked to my friend for help. He smiled wanly and ruddered right, turning the sun out of my face. He has a kind heart, but there was nothing else for him to do. I was seasick.

Anyone who has been really seasick will know that I am speaking of the most horrible living eternity of suffering. No matter how soon it is over, it will have lasted too long.

These days, there are in-a-pill-hidden potions that work quite well, but some of the old prescriptions are fascinating, even frightening: an ounce of cayenne pepper boiled in bouillon, mustard leaf tea double-strength and thickened with flour, an ice bag on the base of the spine, a pint of sea water swallowed in one gulp, a one-inch cube of pork fat fried with fresh garlic. But the most ingenious, and expensive, assault on Citadel Maldemer was dreamed and paid for by Sir Henry Bessemer, inventor of the steelmiller’s blast furnace.

These days, there are in-a-pill-hidden potions that work quite well, but some of the old prescriptions are fascinating, even frightening: an ounce of cayenne pepper boiled in bouillon, mustard leaf tea double-strength and thickened with flour, an ice bag on the base of the spine, a pint of sea water swallowed in one gulp, a one-inch cube of pork fat fried with fresh garlic. But the most ingenious, and expensive, assault on Citadel Maldemer was dreamed and paid for by Sir Henry Bessemer, inventor of the steelmiller’s blast furnace.

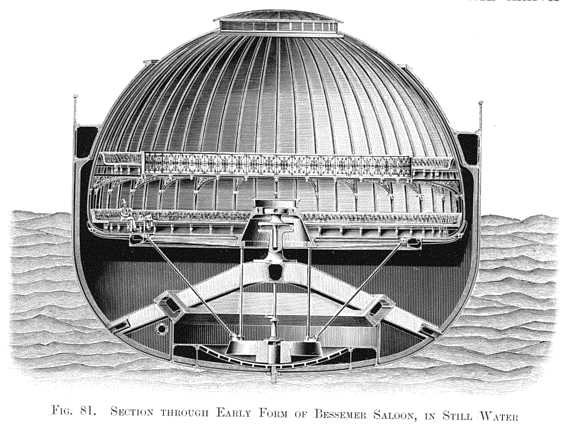

Picture the English Channel on a bright and bouncy March afternoon, waves rounded and following one upon the other like rolls on innumerable baby thighs. Visualize our industrious 19th Century industrial knight losing a particularly dreadful contest within his inner ear and resolving to quease no more. Out of this stalwart resolve came the idea for the steamship Bessemer in which a giant passenger cabin (the saloon) would be hung on gimbals (pivots, axles, or look it up) enabling it to remain upright and steady even as the ship rolled through the roughest seas.

Bessemer, normally steely and conservative, ignored the unalloyed skepticism of scientists, shipwrights, and engineers. He forged on…unaware of the ironies milling just over the horizon.

Gilded, tapestried, and chandeliered, the Bessemer, with its ship-inside-a-ship cost a fortune to build, and on its maiden voyage in 1873 nothing went right. Physically speaking, Sir Henry’s mistake was an underestimation of angular momentum’s passion to conserve itself. At first, as designed, the jounce of the sea embraced only the outer hull while dignitaries in the passenger compartment, standing smugly on one foot, salooned champagne. But friction and Newton, two ubiquitous demons, teamed. Radian by radian the outer rocking inexorably transferred itself to the passenger cabin until it was the Bessemer that hove steady through the waves while the earls and their ladies were double-time osterized within, Neptune’s blender button set to puree.

Gilded, tapestried, and chandeliered, the Bessemer, with its ship-inside-a-ship cost a fortune to build, and on its maiden voyage in 1873 nothing went right. Physically speaking, Sir Henry’s mistake was an underestimation of angular momentum’s passion to conserve itself. At first, as designed, the jounce of the sea embraced only the outer hull while dignitaries in the passenger compartment, standing smugly on one foot, salooned champagne. But friction and Newton, two ubiquitous demons, teamed. Radian by radian the outer rocking inexorably transferred itself to the passenger cabin until it was the Bessemer that hove steady through the waves while the earls and their ladies were double-time osterized within, Neptune’s blender button set to puree.

Alerted by the screams and curses, the captain turned the Bessemer around. But its constantly shifting weight made it impossible to control. In docking, it destroyed its dock.

Eventually Bessemer gave up, convinced at last that the old sailor was right. “The only cure for seasickness is a dose of dry land.”

Seagull photo © Sezai Samhay