Scores of articles have been written to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Lincoln’s birth. One of the most interesting appeared in the February 2009 issue of Smithsonian magazine. I reprint it here in its entirety. The images and links are my choices.

Lincoln’s Contested Legacy

Lincoln’s Contested Legacy

Great Emancipator or unreconstructed racist? Defender of civil liberties or subverter of the Constitution? Each generation evokes a different Lincoln. But who was he?

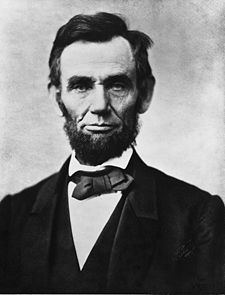

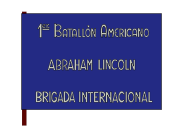

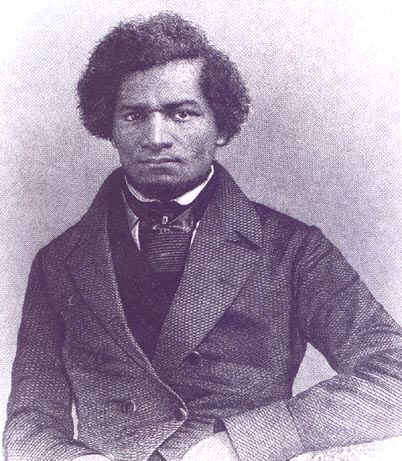

From the time of his death in 1865 to the 200th anniversary of his birth, February 12, 2009, there has never been a decade in which Abraham Lincoln‘s influence has not been felt. Yet it has not been a smooth, unfolding history, but a jagged narrative filled with contention and revisionism. Lincoln’s legacy has shifted again and again as different groups have interpreted him. Northerners and Southerners, blacks and whites, East Coast elites and prairie Westerners, liberals and conservatives, the religious and secular, scholars and popularizers-all have recalled a sometimes startlingly  different Lincoln. He has been lifted up by both sides of the Temperance Movement; invoked for and against federal intervention in the economy; heralded by anti-communists, such as Senator Joseph McCarthy, and by American communists, such as those who joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the fight against the fascist Spanish government in the 1930s. Lincoln has been used to justify support for and against incursions on civil liberties, and has been proclaimed both a true and a false friend to African-Americans. Was he at heart a “progressive man” whose death was an “unspeakable calamity” for African-Americans, as Frederick Douglass insisted in 1865? Or was he “the embodiment…of the American Tradition of racism,” as African-American writer Lerone Bennett Jr. sought to document in a 2000 book?

different Lincoln. He has been lifted up by both sides of the Temperance Movement; invoked for and against federal intervention in the economy; heralded by anti-communists, such as Senator Joseph McCarthy, and by American communists, such as those who joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the fight against the fascist Spanish government in the 1930s. Lincoln has been used to justify support for and against incursions on civil liberties, and has been proclaimed both a true and a false friend to African-Americans. Was he at heart a “progressive man” whose death was an “unspeakable calamity” for African-Americans, as Frederick Douglass insisted in 1865? Or was he “the embodiment…of the American Tradition of racism,” as African-American writer Lerone Bennett Jr. sought to document in a 2000 book?

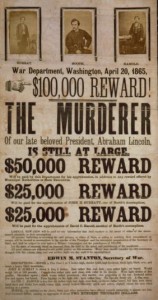

It is often argued that Lincoln’s abiding reputation is the result of his martyrdom. And certainly the assassination, occurring as it did on Good Friday, propelled him into reverential heights. Speaking at a commemoration at the Athenaeum Club in New York City on April 18, 1865, three days after Lincoln died, Parke Godwin, editor of the Evening Post, summed up the prevailing mood. “No loss has been comparable to his,” Godwin said. “Never in human history has there been so universal, so spontaneous, so profound an expression of a nation’s bereavement.” He was the first American president to be assassinated, and waves of grief touched every type of neighborhood and every class-at least in the North. But the shock at the murder explains only part of the tidal wave of mourning. It is hard to imagine that the assassination of James Buchanan or Franklin Pierce would have had the same impact on the national psyche. The level of grief reflected who Lincoln was and what he had come to represent. “Through all his public function,” Godwin said, “there shone the fact that he was a wise and good man…. [He was] our supremest leader-our safest counsellor-our wisest friend-our dear father.”

It is often argued that Lincoln’s abiding reputation is the result of his martyrdom. And certainly the assassination, occurring as it did on Good Friday, propelled him into reverential heights. Speaking at a commemoration at the Athenaeum Club in New York City on April 18, 1865, three days after Lincoln died, Parke Godwin, editor of the Evening Post, summed up the prevailing mood. “No loss has been comparable to his,” Godwin said. “Never in human history has there been so universal, so spontaneous, so profound an expression of a nation’s bereavement.” He was the first American president to be assassinated, and waves of grief touched every type of neighborhood and every class-at least in the North. But the shock at the murder explains only part of the tidal wave of mourning. It is hard to imagine that the assassination of James Buchanan or Franklin Pierce would have had the same impact on the national psyche. The level of grief reflected who Lincoln was and what he had come to represent. “Through all his public function,” Godwin said, “there shone the fact that he was a wise and good man…. [He was] our supremest leader-our safest counsellor-our wisest friend-our dear father.”

Not everyone agreed. Northern Democrats had been deeply opposed to Lincoln’s wartime suspension of habeas corpus, which led to the imprisonment without trial of thousands of  suspected traitors and war protesters. Though Lincoln had taken care to proceed constitutionally and with restraint, his opponents decried his “tyrannical” rule. But in the wake of the assassination even his critics were silent.

suspected traitors and war protesters. Though Lincoln had taken care to proceed constitutionally and with restraint, his opponents decried his “tyrannical” rule. But in the wake of the assassination even his critics were silent.

Across much of the South, of course, Lincoln was hated, even in death. Though Robert E. Lee and many Southerners expressed regret over the murder, others saw it as an act of Providence, and cast John Wilkes Booth as the bold slayer of an American tyrant. “All honor to J. Wilkes Booth,” wrote Southern diarist Kate Stone (referring as well to the simultaneous, though not fatal, attack on Secretary of State William Seward): “What torrents of blood Lincoln has caused to flow, and how Seward has aided him in his bloody work. I cannot be sorry for their fate. They deserve it. They have reaped their just reward.”

Four years after Lincoln’s death, Massachusetts journalist Russell Conwell found widespread, lingering bitterness toward Lincoln in the ten former Confederate states that Conwell visited. “Portraits of Jeff Davis and Lee hang in all their parlors, decorated with Confederate flags,” he wrote. “Photographs of Wilkes Booth, with the last words of great martyrs printed upon its borders; effigies of Abraham Lincoln hanging by the neck…adorn their drawing rooms.” The Rebellion here “seems not to be dead yet,” Conwell concluded.

Four years after Lincoln’s death, Massachusetts journalist Russell Conwell found widespread, lingering bitterness toward Lincoln in the ten former Confederate states that Conwell visited. “Portraits of Jeff Davis and Lee hang in all their parlors, decorated with Confederate flags,” he wrote. “Photographs of Wilkes Booth, with the last words of great martyrs printed upon its borders; effigies of Abraham Lincoln hanging by the neck…adorn their drawing rooms.” The Rebellion here “seems not to be dead yet,” Conwell concluded.

For their part, African-Americans’ pangs of loss were tinged with fear for their future. Few promoted Lincoln’s legacy more passionately than critic-turned-admirer Frederick Douglass, whose frustration at the presidency of Andrew Johnson kept growing. Lincoln was “a progressive man, a human man, an honorable man, and at heart an antislavery man,” Douglass wrote in December 1865. “I assume…had Abraham Lincoln been spared to see this day, the negro of the South would have had more hope of enfranchisement.” Ten years later, at the dedication of the Freedmen’s Memorial in Washington, D.C., Douglass seemed to recant these words, calling Lincoln “preeminently the white man’s President” and American blacks “at best only his step-children.” But Douglass’ purpose that day was to puncture the sentimentality of the occasion and to criticize the government’s abandonment of Reconstruction. And in the final decades of his long life Douglass repeatedly invoked Lincoln as having embodied the spirit of racial progress.

Douglass’ worries about America proved prophetic. By the 1890s, with the failure of Reconstruction and the advent of Jim Crow, Lincoln’s legacy of emancipation lay in ruins. Regional reconciliation-the healing of the rift between North and South-had supplanted the nation’s commitment to civil rights. In 1895, at a gathering of Union and Confederate soldiers in Chicago, the topics of slavery and race were set aside in favor of a focus on North-South reconciliation. As the 1909 centennial of Lincoln’s birth approached, race relations in the country were reaching a nadir.

Douglass’ worries about America proved prophetic. By the 1890s, with the failure of Reconstruction and the advent of Jim Crow, Lincoln’s legacy of emancipation lay in ruins. Regional reconciliation-the healing of the rift between North and South-had supplanted the nation’s commitment to civil rights. In 1895, at a gathering of Union and Confederate soldiers in Chicago, the topics of slavery and race were set aside in favor of a focus on North-South reconciliation. As the 1909 centennial of Lincoln’s birth approached, race relations in the country were reaching a nadir.

In August 1908, riots broke out in Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield, Illinois, after a white woman, Mabel Hallam, claimed she had been raped by a local black man, George Richardson. (She later admitted to making up the story.) On Friday, August 14, two thousand white men and boys began to attack African-Americans and set fire to black businesses. “Lincoln freed you,” rioters were heard to yell. “We’ll show you where you belong.” The next night, the mob approached the shop of William Donnegan, a 79-year-old African-American shoemaker who had made boots for Lincoln and at whose brother’s barbershop Lincoln used to mingle with African-Americans. Setting fire to Donnegan’s shop, the mob dragged the old man outside and  pelted him with bricks, then slashed his throat. Still alive, he was dragged across the street into a school courtyard. There, not far from a statue of Abraham Lincoln, he was hoisted up a tree and left to die.

pelted him with bricks, then slashed his throat. Still alive, he was dragged across the street into a school courtyard. There, not far from a statue of Abraham Lincoln, he was hoisted up a tree and left to die.

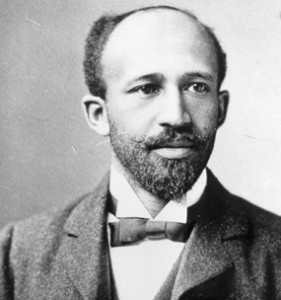

Horrified by the reports of such ugly violence, a group of New York City activists formed the National Negro Committee, soon to be renamed the NAACP, with a young scholar named W.E.B. Du Bois to serve as director of publicity and research. From its beginning, the organization’s mission was intertwined with Lincoln’s, as one of its early statements made clear: “Abraham Lincoln began the emancipation of the Negro American. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People proposes to complete it.”

Horrified by the reports of such ugly violence, a group of New York City activists formed the National Negro Committee, soon to be renamed the NAACP, with a young scholar named W.E.B. Du Bois to serve as director of publicity and research. From its beginning, the organization’s mission was intertwined with Lincoln’s, as one of its early statements made clear: “Abraham Lincoln began the emancipation of the Negro American. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People proposes to complete it.”

The centennial of Lincoln’s birth marked the largest commemoration of any person in American history. The Lincoln penny was minted, the first coin bearing the image of an American president, and talks took place in Washington about a grand Lincoln monument to be erected in the nation’s capital. All across the country, and in many nations around the world, America’s 16th president was extolled. An editorial in the London Times declared, “Together with Washington, Lincoln occupies a pinnacle to which no third person is likely to attain.” The commander of the Brazilian Navy ordered a 21-gun salute “in homage to the memory of that noble martyr of moral and of neighborly love.” The former states of the Confederacy, which less than 50 years earlier had rejoiced at Lincoln’s death, now paid tribute to the leader who had reunified the nation. W. C. Calland, a state official in Missouri-which, during the Civil War, had been a border state that contributed 40,000 troops to the Confederate cause-barely contained his astonishment in a memorandum reporting on the festivities: “Perhaps no event could have gathered around it so much of patriotic sentiment in the South as the birthday of Abraham Lincoln….Confederate veterans held public services and gave public expression to the sentiment, that had ‘Lincoln lived’ the days of reconstruction might have been softened and the era of good feeling ushered in earlier.”

In most of America the celebrations were thoroughly segregated, including in Springfield, where blacks (with the exception of a declined invitation to Booker T. Washington) were excluded from a dazzling gala dinner. As the Chicago Tribune reported, it “is to be a lily white affair from start to finish.” Across town, inside one of Springfield’s most prominent black churches, African-Americans met for their own celebration. “We colored people love and revere the memory of Lincoln,” said the Rev. L. H. Magee. “His name is a synonym for the freedom of wife, husband and children, and a chance to live in a free country, fearless of the slave-catcher and his  bloodhounds.” Referring to the “sacred dust of the great emancipator” lying in Springfield’s Oak Ridge Cemetery, Magee called upon black people across America to make pilgrimages to Lincoln’s tomb. And he cast his gaze forward a hundred years-to the bicentennial of 2009-and envisioned a Lincoln celebration “by the great-grandchildren of those who celebrate this centenary.” In that far-off year, Magee predicted, “prejudice shall have been banished as a myth and relegated to the dark days of ‘Salem witchcraft.’ ”

bloodhounds.” Referring to the “sacred dust of the great emancipator” lying in Springfield’s Oak Ridge Cemetery, Magee called upon black people across America to make pilgrimages to Lincoln’s tomb. And he cast his gaze forward a hundred years-to the bicentennial of 2009-and envisioned a Lincoln celebration “by the great-grandchildren of those who celebrate this centenary.” In that far-off year, Magee predicted, “prejudice shall have been banished as a myth and relegated to the dark days of ‘Salem witchcraft.’ ”

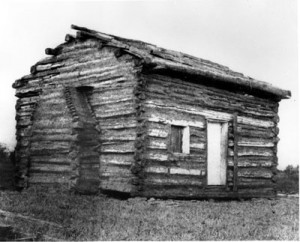

A notable exception to the rule of segregated commemorations took place in Kentucky, where President Theodore Roosevelt, a longtime Lincoln admirer, presided over a dramatic ceremony at the old Lincoln homestead. Lincoln’s birth cabin, of dubious provenance, had been purchased from promoters who had been displaying it around the country. Now the state, with Congressional support, planned to rebuild it on its original site, on a knoll above the Sinking Spring that had originally attracted Thomas Lincoln, the president’s father, to the property. The 110-acre farmstead would become the “nation’s commons,” it was declared-a crossroads linking the entire country.

A notable exception to the rule of segregated commemorations took place in Kentucky, where President Theodore Roosevelt, a longtime Lincoln admirer, presided over a dramatic ceremony at the old Lincoln homestead. Lincoln’s birth cabin, of dubious provenance, had been purchased from promoters who had been displaying it around the country. Now the state, with Congressional support, planned to rebuild it on its original site, on a knoll above the Sinking Spring that had originally attracted Thomas Lincoln, the president’s father, to the property. The 110-acre farmstead would become the “nation’s commons,” it was declared-a crossroads linking the entire country.

Seven thousand people showed up for the dedication, including a number of African-Americans, who mixed in among the others with no thought of separation. When Roosevelt began his speech he hopped onto a chair and was greeted by cheers. “As the years [roll] by,” he said in his crisp, excitable voice, “…this whole Nation will grow to feel a peculiar sense of pride in the mightiest of the mighty men who mastered the mighty days; the lover of his country and of all mankind; the man whose blood was shed for the union of his people and for the freedom of a race: Abraham Lincoln.” The ceremony in Kentucky heralded the possibility of national reconciliation and racial justice proceeding hand in hand. But that was not to be, as the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. 13 years later would make all too clear.

Members of the Lincoln Memorial commission—created by Congress in 1911—saw the monument not only as a tribute to the 16th president but also as a symbol of a reunified nation. With Northerners and Southerners having fought side by side in the Spanish-American War of 1898 and again in World War I, it was time, they felt, to put aside sectional differences once and for all. This meant that the Lincoln honored on the National Mall must not be the man who had broken the South militarily or had crushed the institution of slavery but the preserver of the Union. “By emphasizing his saving the Union you appeal to both sections,” wrote Royal Cortissoz, author of the inscription that would be etched inside the finished building behind Daniel Chester French‘s nearly 20-foot-tall sculpture of the seated Lincoln. “By saying nothing about slavery you avoid the rubbing of old sores.”

Members of the Lincoln Memorial commission—created by Congress in 1911—saw the monument not only as a tribute to the 16th president but also as a symbol of a reunified nation. With Northerners and Southerners having fought side by side in the Spanish-American War of 1898 and again in World War I, it was time, they felt, to put aside sectional differences once and for all. This meant that the Lincoln honored on the National Mall must not be the man who had broken the South militarily or had crushed the institution of slavery but the preserver of the Union. “By emphasizing his saving the Union you appeal to both sections,” wrote Royal Cortissoz, author of the inscription that would be etched inside the finished building behind Daniel Chester French‘s nearly 20-foot-tall sculpture of the seated Lincoln. “By saying nothing about slavery you avoid the rubbing of old sores.”

Two American presidents—Warren G. Harding and William Howard Taft—took part in the dedication ceremonies held on May 30, 1922, and loudspeakers on the memorial’s rooftop carried the festivities across the Mall. Black guests were seated in a “colored section” off to the side. The commissioners had included a black speaker in the program; not wanting an activist who might challenge the mostly white audience, they had chosen Robert Russa Moton, the mild-mannered president of Tuskegee Institute, and required him to submit his text in advance for revision. But in what turned out to be the most powerful speech of the day, Moton highlighted Lincoln’s emancipationist legacy and challenged Americans to live up to their calling to be a people of “equal justice and equal opportunity.”

Two American presidents—Warren G. Harding and William Howard Taft—took part in the dedication ceremonies held on May 30, 1922, and loudspeakers on the memorial’s rooftop carried the festivities across the Mall. Black guests were seated in a “colored section” off to the side. The commissioners had included a black speaker in the program; not wanting an activist who might challenge the mostly white audience, they had chosen Robert Russa Moton, the mild-mannered president of Tuskegee Institute, and required him to submit his text in advance for revision. But in what turned out to be the most powerful speech of the day, Moton highlighted Lincoln’s emancipationist legacy and challenged Americans to live up to their calling to be a people of “equal justice and equal opportunity.”

In the days that followed, Moton’s speech went almost entirely unreported. Even his name was dropped from the record—in most accounts Moton was referred to simply as “a representative of the race.” African-Americans across the country were outraged. The Chicago Defender, an African-American weekly, urged a boycott of the Lincoln Memorial until it was properly dedicated to the real Lincoln. Not long afterward, at a large gathering in front of the monument, Bishop E.D.W. Jones, an African-American religious leader, insisted that “the immortality of the great emancipator lay not in his preservation of the Union, but in his giving freedom to the negroes of America.”

urged a boycott of the Lincoln Memorial until it was properly dedicated to the real Lincoln. Not long afterward, at a large gathering in front of the monument, Bishop E.D.W. Jones, an African-American religious leader, insisted that “the immortality of the great emancipator lay not in his preservation of the Union, but in his giving freedom to the negroes of America.”

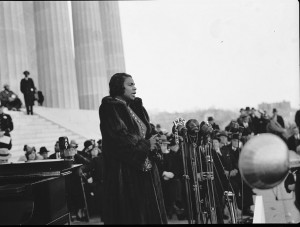

In the decades since, the Lincoln Memorial has been the scene of many dramatic moments in history. A photograph of President Franklin D. Roosevelt taken at the memorial on February 12, 1938, shows him leaning against a military attaché, his hand on his heart. “I do not know which party Lincoln would belong to if he were alive,” Roosevelt said two years later. “His sympathies and his motives of championship of humanity itself have made him for all centuries to come the legitimate property of all parties-of every man and woman and child in every part of our land.” On April 9, 1939, after being denied the use of Constitution Hall in Washington because of her race, the great contralto Marian Anderson was invited to sing at the Lincoln Memorial. Seventy-five thousand people, black and white, gathered at the monument for an emotional concert that further linked Lincoln’s memory to racial progress. Three years later, during the bleak days of World War II, when it seemed that the Allies might lose the war, Lincoln’s memory served as a potent force of national encouragement. In July 1942, on an outdoor stage within view of the Lincoln Memorial, a powerful performance of Aaron Copland‘s “Lincoln Portrait” took place, with Carl Sandburg reading Lincoln’s words, including “we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain.”

In the decades since, the Lincoln Memorial has been the scene of many dramatic moments in history. A photograph of President Franklin D. Roosevelt taken at the memorial on February 12, 1938, shows him leaning against a military attaché, his hand on his heart. “I do not know which party Lincoln would belong to if he were alive,” Roosevelt said two years later. “His sympathies and his motives of championship of humanity itself have made him for all centuries to come the legitimate property of all parties-of every man and woman and child in every part of our land.” On April 9, 1939, after being denied the use of Constitution Hall in Washington because of her race, the great contralto Marian Anderson was invited to sing at the Lincoln Memorial. Seventy-five thousand people, black and white, gathered at the monument for an emotional concert that further linked Lincoln’s memory to racial progress. Three years later, during the bleak days of World War II, when it seemed that the Allies might lose the war, Lincoln’s memory served as a potent force of national encouragement. In July 1942, on an outdoor stage within view of the Lincoln Memorial, a powerful performance of Aaron Copland‘s “Lincoln Portrait” took place, with Carl Sandburg reading Lincoln’s words, including “we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain.”

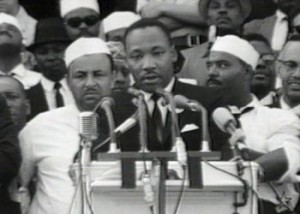

In 1957, a 28-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. came to the Lincoln Memorial to help lead a protest for black voting rights. “The spirit of Lincoln still lives,” he had proclaimed before the protest. Six years later, in 1963, he returned for the March on Washington. The August day was bright and sunny, and more than 200,000 people, black and white, converged on the Mall in front of the Lincoln Memorial. King’s speech called Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation “a beacon of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been scarred in the flame of withering injustice.” But it was not enough, he went on, simply to glorify the past. “One hundred years later we must face the tragic fact the Negro is still not free….is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chain of discrimination.” And then he told the enraptured crowd, “I have a dream.” Author and New York Times book critic Richard Bernstein later called King’s words “the single most important piece of American oratory since Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.”

In 1957, a 28-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. came to the Lincoln Memorial to help lead a protest for black voting rights. “The spirit of Lincoln still lives,” he had proclaimed before the protest. Six years later, in 1963, he returned for the March on Washington. The August day was bright and sunny, and more than 200,000 people, black and white, converged on the Mall in front of the Lincoln Memorial. King’s speech called Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation “a beacon of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been scarred in the flame of withering injustice.” But it was not enough, he went on, simply to glorify the past. “One hundred years later we must face the tragic fact the Negro is still not free….is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chain of discrimination.” And then he told the enraptured crowd, “I have a dream.” Author and New York Times book critic Richard Bernstein later called King’s words “the single most important piece of American oratory since Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.”

Just three months after the speech, President John F. Kennedy would be assassinated, ushering in a period of national grief not unlike that after Lincoln’s murder. Also echoing the previous century, Kennedy’s efforts to advance civil rights had prompted some to mourn him as the “second emancipator.” A. Philip Randolph, who had organized the March on Washington, declared that the time had come to complete “this unfinished business of American democracy for which two presidents have died.”

Just three months after the speech, President John F. Kennedy would be assassinated, ushering in a period of national grief not unlike that after Lincoln’s murder. Also echoing the previous century, Kennedy’s efforts to advance civil rights had prompted some to mourn him as the “second emancipator.” A. Philip Randolph, who had organized the March on Washington, declared that the time had come to complete “this unfinished business of American democracy for which two presidents have died.”

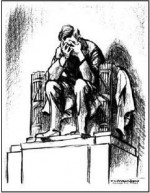

To address a profound need for national healing and unity, JFK’s widow, Jacqueline Kennedy-in consultation with other family members and official planners-decided to model her slain husband’s funeral upon Lincoln’s. The president’s casket was laid in state inside the White House East Room, and was later taken to the Great Rotunda of the Capitol and rested upon the catafalque used at Lincoln’s funeral. On their final procession to Arlington National Cemetery, the funeral cars passed reverently by the Lincoln Memorial. One of the most poignant images from that era was a political cartoon drawn by Bill Mauldin, depicting the statue of Lincoln bent over in grief.

To address a profound need for national healing and unity, JFK’s widow, Jacqueline Kennedy-in consultation with other family members and official planners-decided to model her slain husband’s funeral upon Lincoln’s. The president’s casket was laid in state inside the White House East Room, and was later taken to the Great Rotunda of the Capitol and rested upon the catafalque used at Lincoln’s funeral. On their final procession to Arlington National Cemetery, the funeral cars passed reverently by the Lincoln Memorial. One of the most poignant images from that era was a political cartoon drawn by Bill Mauldin, depicting the statue of Lincoln bent over in grief.

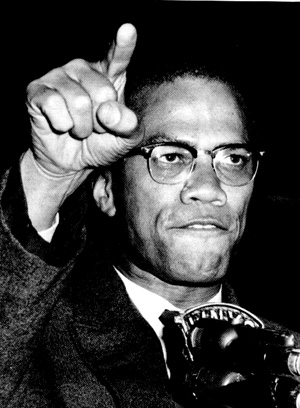

In the nearly half century since, Lincoln’s reputation has been under assault from various quarters. Malcolm X broke with the long tradition of African-American admiration for Lincoln, saying in 1964 that he had done “more to trick Negroes than any other man in history.”

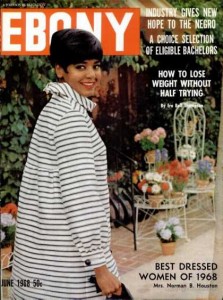

In the nearly half century since, Lincoln’s reputation has been under assault from various quarters. Malcolm X broke with the long tradition of African-American admiration for Lincoln, saying in 1964 that he had done “more to trick Negroes than any other man in history.”  In 1968, pointing to clear examples of Lincoln’s racial prejudice, Lerone Bennett Jr. asked in Ebony magazine, “Was Abe Lincoln a White Supremacist?” (His answer: yes.) The 1960s and ’70s were a period in which icons of all kinds-especially great leaders of the past-were being smashed, and Lincoln was no exception. Old arguments surfaced that he had never really cared about emancipation, that he was at heart a political opportunist. States’ rights libertarians criticized his aggressive handling of the Civil War, his assaults on civil liberties and his aggrandizing of federal government.

In 1968, pointing to clear examples of Lincoln’s racial prejudice, Lerone Bennett Jr. asked in Ebony magazine, “Was Abe Lincoln a White Supremacist?” (His answer: yes.) The 1960s and ’70s were a period in which icons of all kinds-especially great leaders of the past-were being smashed, and Lincoln was no exception. Old arguments surfaced that he had never really cared about emancipation, that he was at heart a political opportunist. States’ rights libertarians criticized his aggressive handling of the Civil War, his assaults on civil liberties and his aggrandizing of federal government.

In particular, the Nixon administration’s perceived abuse of executive power during the Vietnam War prompted unflattering comparisons with Lincoln’s wartime measures. Some scholars, however, rejected such comparisons, noting that Lincoln reluctantly did what he thought necessary to preserve the Constitution and the nation. Historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., for one, wrote in 1973 that since the Vietnam War didn’t rise to the same level of national crisis, Nixon “has sought to establish as a normal Presidential power what previous Presidents had regarded as power justified only by extreme emergencies. . . . He does not, like Lincoln, confess to doubt about the legality of his course.”

Decades later, another war would again bring Lincoln’s legacy to the fore. Shortly after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush addressed Congress with words evocative of Lincoln’s comments at the outset of the Civil War: “The course of this conflict is not known,” Bush said, “yet its outcome is certain. Freedom and fear, justice and cruelty, have always been at war, and we know that God is not neutral between them.” As in the Vietnam era, subsequent controversies over the White House’s conduct of the war on terror-such as the use of secret wiretapping and the detention of “enemy combatants” without trial-provoked another round of debates over presidential powers and the precedents created by Lincoln.

Despite such lingering controversies, Lincoln has consistently polled as one of the three greatest U.S. presidents, along with George Washington and Franklin D. Roosevelt. And though many African-Americans lost their veneration for him over the decades, recent statements by President Barack Obama and others suggest renewed appreciation. It was black Americans, after all, who refused to give up on Lincoln’s emancipationist legacy even when American whites wanted to forget it. And if Lincoln shared in the racial prejudice of his day, it is also true that his outlook grew significantly over the years of his presidency. He was “the first great man that I talked with in the United States freely,” Frederick Douglass wrote, “who in no single instance reminded me of the difference between himself and myself, of the difference of color.”

And yet, as Bennett and others have rightly insisted, the Lincoln of earlier generations of blacks was also in part a mythic figure—his own racial prejudices passed over too lightly, even as African-Americans’ roles in emancipation were underemphasized. In a series of 1922 editorials for the NAACP journal the Crisis, W.E.B. Du Bois stressed the importance of taking Lincoln off his pedestal in order to place attention on the need for ongoing progress. But Du Bois refused to reject Lincoln in the process. “The scars and foibles and contradictions of the Great do not diminish but enhance the worth and meaning of their upward struggle,” he wrote. Of all the great figures of the 19th century, “Lincoln is to me the most human and lovable. And I love him not because he was perfect but because he was not and yet triumphed.” In a 2005 essay in Time magazine, Obama said much the same thing: “I am fully aware of his limited views on race. But…[in] the midst of slavery’s dark storm and the complexities of governing a house divided, he somehow kept his moral compass pointed firm and true.”

Lincoln will always remain the president who helped destroy slavery and preserved the Union. With stubbornness, caution and an exquisite sense of timing, he engaged almost physically with unfolding history. Derided by some as an opportunist, he was in fact an artist, responding to events as he himself changed over time, allowing himself to grow into a true reformer. Misjudged as a mere jokester, incompetent, unserious, he was in fact the most serious actor on the political stage. He was politically shrewd, and he took a long view of history. And he knew when to strike to obtain his ends. Just for his work on behalf of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery in the United States, he has earned a permanent place in the history of human freedom.

In addition, he was a man of patience who refused to demonize others; a person of the middle who could build bridges across chasms. Herein may lie one of his most important legacies-his unwavering desire to reunite the American people. In Chicago’s Grant Park, the night he was declared the winner of the 2008 election, Obama sought to capture that sentiment, quoting from Lincoln’s first inaugural address: “We are not enemies, but friends…. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection.”

And with the inauguration of the nation’s first African-American president, we remember that, in 1864, with the Union war effort going badly, the national government might have been tempted to suspend the upcoming elections. Not only did Lincoln insist they take place, he staked his campaign on a controversial platform calling for the 13th Amendment, willing to risk everything on its behalf. When he went on to an overwhelming victory in November, he obtained a mandate to carry through his program. “[I]f the rebellion could force us to forego, or postpone a national election,” he spoke to a gathered crowd from a White House window, “it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us….[The election] has demonstrated that a people’s government can sustain a national election, in the midst of a great civil war.”

Around the world, governments routinely suspend elections, citing the justification of a “national emergency.” Yet Lincoln set a precedent that would guarantee the voting rights of the American people through subsequent wars and economic depressions. Though our understanding of him is more nuanced than it once was, and we are more able to recognize his limitations as well as his strengths, Abraham Lincoln remains the great example of democratic leadership-by most criteria, truly our greatest president.

Around the world, governments routinely suspend elections, citing the justification of a “national emergency.” Yet Lincoln set a precedent that would guarantee the voting rights of the American people through subsequent wars and economic depressions. Though our understanding of him is more nuanced than it once was, and we are more able to recognize his limitations as well as his strengths, Abraham Lincoln remains the great example of democratic leadership-by most criteria, truly our greatest president.

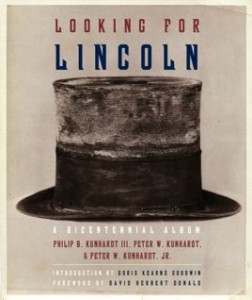

Philip B. Kunhardt III is co-author of the 2008 book Looking for Lincoln and a Bard Center Fellow.