The following essay is taken without alteration from Harvard Magazine’s current issue. I reprint it without comment because its clarity and persuasiveness require none.

Read and reflect.

* * * * *

Porter  University Professor Helen Vendler, a preeminent poetry critic, has served on Harvard College’s undergraduate admissions committee. Given contemporary admissions processes and pressures, she recalls “wondering how well T.S. Eliot (who had to do a preparatory year at Milton Academy before he could risk admittance, and whose mother was in consultation with Harvard and Milton officials before deciding what to do with him after he finished high school in St. Louis) would have fared, or Wallace Stevens (admitted as a special student to do only three years’ study), or E.E. Cummings (admittedly, a faculty child).” Accordingly, she proposed that alumni interviewers receive some guidance on how to understand, attract, and evaluate applicants whose creative talents might otherwise be overlooked, and wrote this essay, subsequently posted on Harvard’s Office of Admissions website.

University Professor Helen Vendler, a preeminent poetry critic, has served on Harvard College’s undergraduate admissions committee. Given contemporary admissions processes and pressures, she recalls “wondering how well T.S. Eliot (who had to do a preparatory year at Milton Academy before he could risk admittance, and whose mother was in consultation with Harvard and Milton officials before deciding what to do with him after he finished high school in St. Louis) would have fared, or Wallace Stevens (admitted as a special student to do only three years’ study), or E.E. Cummings (admittedly, a faculty child).” Accordingly, she proposed that alumni interviewers receive some guidance on how to understand, attract, and evaluate applicants whose creative talents might otherwise be overlooked, and wrote this essay, subsequently posted on Harvard’s Office of Admissions website.

Anyone who has seen application folders knows the talents of our potential undergraduates, as well as the difficulties overcome by many of them. And anyone who teaches our undergraduates, as I have done for over 30 years, knows the delight of encountering them. Each of us has responded warmly to many sorts of undergraduates: I’ve encountered the top Eagle Scout in the country, a violinist who is now part of a young professional quartet, a student who backpacked solo through Tierra del Fuego, and other memorable writers, pre-meds, theater devotees, Lampoon contributors on their way to Hollywood, and more. They have come from both private and public schools and from foreign countries.

We hear from all sides about “leadership,” “service,” “scientific passion,” and various other desirable qualities that bring about change in the world. The fields that receive the most media attention (economics, biology, technology, political theory, psychology) occupy the public mind more than fields—perhaps more influential in the long run—in the humanities: poetry, philosophy, foreign languages, drama. W.H. Auden famously said—after seeing the Spanish Civil War—that “poetry makes nothing happen.” And it doesn’t, when the “something” desired is the end of hostilities, a government coup, an airlift, or an election victory. But those “somethings” are narrowly conceived. The cultural resonance of the characters of Greek epic and tragedy—Achilles, Oedipus, An tigone—and the crises of consciousness they embody—have been felt long after the culture that gave them birth has disappeared. Gandhi’s philosophical conception of nonviolent resistance has penetrated far beyond his own country and beyond his own century. Music makes nothing happen, either, in the world of reportable events (which is the media world); but the permanence of Beethoven in revolutionary consciousness has not been shaken. We would know less of New England without Emily Dickinson’s “seeing New Englandly,” as she put it. Books are still considering Lincoln’s speeches—the Gettysburg Address, the Second Inaugural—long after the events that prompted them vanished into the past. Nobody would remember the siege of Troy if Homer had not sung it, or Guernica if Picasso had not painted it. The Harlem Renaissance would not have occurred as it did without the stimulus of Alain Locke, Harvard’s first black Rhodes Scholar. Modern philosophy of mind would not exist as it does without the rigors of Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, nor would our idea of women’s rights have taken the shape it has without Woolf’s claim for a room of her own.

We are eager to harbor the next Homer, the next Kant, or the next Dickinson. There is no reason why we shouldn’t expect such a student to spend his or her university years with us. Emerson did; Wallace Stevens did; Robert Frost did; Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery and Fairfield Porter and Adrienne Rich did; and had universities harbored women in residence when Dickinson came of age, she might have been glad to be here. She and Woolf could be the writers they were because their fathers had extensive private libraries; women without such resources were deprived of the chance to be all they could be. Universities are the principal educators, now, of men and women alike, and they produce the makers of culture. Makers of culture last longer in public memory than members of Parliament, representatives, and senators; they modify the mind of their century more, in general, than elected officials. They make the reputation of a country. Michelangelo outlasts the Medici and the popes in our idea of Italy; and, as one French poet said, “le buste/ Survit à la cité”: art outlives the cities that gave it birth.

In the future, will the United States be remembered with admiration? Will we be thanked for our stock market and its investors? For our wars and their consequences? For our depletion of natural resources? For our failure at criminal rehabilitation? Certainly not. Future cultures will be grateful to us for many aspects of scientific discovery, and for our progress (such as it has been) toward more humane laws. We can be proud of our graduates who have gone out in the world as devoted investigators of the natural world, or as just judges, or as ministers to the marginalized. But science, the law, and even ethics are fields in motion, constantly surpassing themselves. To future generations our medicine will seem primitive, our laws backward, even our ethical convictions narrow.

“I tried each thing; only some were immortal and free,” wrote our graduate John Ashbery. He decided on the immortal and free things, art and thought, and became a writer who revolutionized the transcription of consciousness in contemporary poetry. Most art, past or present, does not have the stamina to endure; but many of our graduates, like the ones mentioned above, have produced a level of art above the transient. The critical question for us is not whether we are admitting a large number of future doctors and scientists and lawyers and businessmen (even future philanthropists): we are. The question is whether we can attract as many as possible of the future Emersons and Dickinsons. How would we identify them? What should we ask them in interviews? How would we make them want to come to us?

The truth is that many future poets, novelists, and screenwriters are not likely to be straight-A students, either in high school or in college. The arts through which they will discover themselves prize creativity, originality, and intensity above academic performance; they value introspection above extroversion, insight above rote learning. Such unusual students may be, in the long run, the graduates of whom we will be most proud. Do we have room for the reflective introvert as well as for the future leader? Will we enjoy the student who manages to do respectably but not brilliantly in all her subjects but one—but at that one surpasses all her companions? Will we welcome eagerly the person who has in high school been completely uninterested in public service or sports—but who may be the next Wallace Stevens? Can we preach the doctrine of excellence in an art; the doctrine of intellectual absorption in a single field of study; even the doctrine of unsociability; even the doctrine of indifference to money? (Wittgenstein, who was rich, gave all his money away as a distraction; Emily Dickinson, who was rich, appears not to have spent money, personally, on anything except for an occasional dress, and paper and ink.) Can frugality seem as desirable to our undergraduates as affluence—provided it is a frugality that nonetheless allows them enough leisure to think and write? Can we preach a doctrine of vocation in lieu of the doctrine of competitiveness and worldly achievement?

These are crucial questions for Harvard. But there are also other questions we need to ask ourselves: Do we value mostly students who resemble us in talent and personality and choice of interests? Do we remind ourselves to ask, before conversing with a student with artistic or creative interests, what sort of questions will reveal the next T.S. Eliot? (Do we ever ask, “Who is the poet you have most enjoyed reading?” Eliot would have had an interesting answer to that.) Do we ask students who have done well in English which aspects of the English language or a foreign language they have enjoyed learning about, or what books they have read that most touched them? Do we ask students who have won prizes in art whether they ever go to museums? Do we ask in which medium they have felt themselves freest? Do we inquire whether students have artists (writers, composers, sculptors) in their families? Do we ask an introverted student what issues most occupy his mind, or suggest something (justice and injustice in her high school) for her to discuss? Will we believe a recommendation saying, “This student is the most gifted writer I have ever taught,” when the student exhibits, on his transcript, Cs in chemistry and mathematics, and has absolutely no high-school record of group activity? Can we see ourselves admitting such a student (which may entail not admitting someone else, who may have been a valedictorian)?

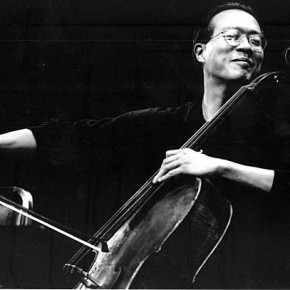

President Drew Faust’s new initiative in the arts [released in late 2008] will make Harvard an immensely attractive place to students with artistic talent of any sort. It remains for us to identify them when they apply—to make sure they can do well enough to gain a degree, yes, but not to expect them to be well-rounded, or to become leaders. Some people in the arts do of course become leaders (they conduct as well as sing, or establish public-service organizations to increase literacy, or work for the reinstatement of the arts in schools). But one can’t quite picture Baudelaire pursuing public service, or Mozart spending time perfecting his mathematics. We need to be deeply attracted to the one-sided as well as the many-sided. Some day the world will be glad we were hospitable to future artists. Of course most of them will not end up as Yo-Yo Ma or Adrienne Rich; but they will be the people who keep the arts alive in our culture. “To have great poets,” as Whitman said, “there must be great audiences too.” The matrix of culture will become impoverished if there are not enough gifted artists and thinkers produced: and since universities are the main nurseries for all the professions, they cannot neglect the professions of art and reflection.

And four years at Harvard can certainly nurture an artist as a more narrowly conceived conservatory education cannot. Great writers and artists have often been deeply (if eccentrically) learned: they have been bilingual or trilingual, or have had a consuming interest in another art (as Whitman loved vocal music, as Michelangelo wrote sonnets). At Harvard, young writers and artists will encounter not only the riches of the course catalog but also numerous others like themselves; such encounters are a prerequisite for the creation of self-confidence in an art. It is no accident that many of our writers have come out of our literary magazines—the Advocate, Persephone, the Gamut, the Harvard Book Review—places where they could find a collective home. Student drama productions, choruses, and orchestras offer comparable homes for the talented. We need such activities and the reflective students who will enable them.

Once we have admitted our potential philosophers, writers, and composers, how will we prepare them for their passage into the wider society? Our excellent students are intensely recruited by business and finance in the fall of their senior year—sometimes even earlier than that. Humanities organizations (foundations, schools, government bureaus) do not have the resources to fly students around the world, or even around the United States, for interviews, nor do their budgets allow for recruiters and their travel expenses. Perhaps money could be found to pay for recruiting trips in the early fall for representatives of humanities organizations. Perhaps we can find a way to convey to our juniors that there are places to go other than Wall Street, and great satisfaction to be found when they follow their own passions, rather than a passion for a high salary. But if we are to be believed when we inform them of such opportunities, we need, I think, to mute our praise for achievement and leadership at least to the extent that we utter equal praise for inner happiness, reflectiveness, and creativity; and we need to invent ways in which our humanities students are actively recruited for jobs suited to their talents and desires.

Once we have admitted our potential philosophers, writers, and composers, how will we prepare them for their passage into the wider society? Our excellent students are intensely recruited by business and finance in the fall of their senior year—sometimes even earlier than that. Humanities organizations (foundations, schools, government bureaus) do not have the resources to fly students around the world, or even around the United States, for interviews, nor do their budgets allow for recruiters and their travel expenses. Perhaps money could be found to pay for recruiting trips in the early fall for representatives of humanities organizations. Perhaps we can find a way to convey to our juniors that there are places to go other than Wall Street, and great satisfaction to be found when they follow their own passions, rather than a passion for a high salary. But if we are to be believed when we inform them of such opportunities, we need, I think, to mute our praise for achievement and leadership at least to the extent that we utter equal praise for inner happiness, reflectiveness, and creativity; and we need to invent ways in which our humanities students are actively recruited for jobs suited to their talents and desires.

With a larger supply of the sort of creativity that yields books and arts, fellow-students whose creativity leans toward scientific experimentation or mathematical speculation will benefit not only from seeing an alternative style of life and thought but also from the sort of intellectual conversation native to writers, composers, painters. America will, in the end, be grateful to us for giving her original philosophers, critics, and artists; and we can let the world see that just as we prize physicians and scientists and lawyers and judges and economists, we also are proud of our future novelists, poets, composers, and critics, who, although they must follow a rather lonely and highly individual path, are indispensable contributors to our nation’s history and reputation.

Helen Vendler is the author, most recently, of Last Looks, Last Books: Stevens, Plath, Lowell, Bishop, Merrill and Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries.