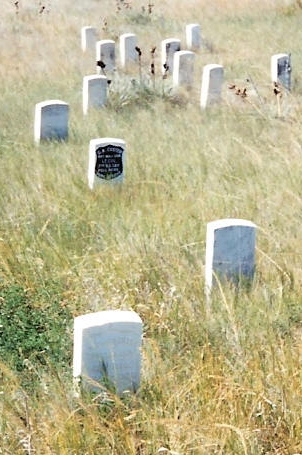

At Little Big Horn National Monument, a low, iron railing surrounds the modest, marble slabs that mark where each white man fell. The fenced rectangle is smaller than my back yard. Custer’s Last Stand…an immense celebration of an ignominious outrage.  The day is overcast, cold, and wet. Forty-eight degrees feels colder in this Great Plains wind. A National Parks ranger gives a spirited description of tactics and weaponry. He almost prances as he gestures across the swales of brown grass, sweeping his hands from side to side to indicate how the advancing Sioux were able to slip from dip to dip without being seen.

The day is overcast, cold, and wet. Forty-eight degrees feels colder in this Great Plains wind. A National Parks ranger gives a spirited description of tactics and weaponry. He almost prances as he gestures across the swales of brown grass, sweeping his hands from side to side to indicate how the advancing Sioux were able to slip from dip to dip without being seen.

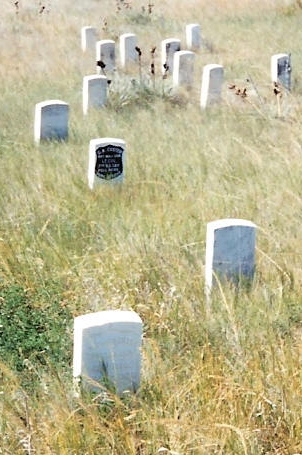

Unlike the other National Parks I’ve visited, this is thoughts and visions, not sights. There is little to see here. Other than the white-on-black face of G. A. Custer’s marker, there is a uniformity in every direction except to the south, where several miles distant, the Montana Interstate reveals just the tops of big rig boxes floating east and west above the long, low hills. This is a small park: a couple of buildings and an attached military cemetery unrelated to The Battle. There is undoubtedly an algorithm that determines who can be interred under the martial exhalations that blow across these hills, but my gravestone investigations reveal no pattern. There are soldiers and wives from many wars.

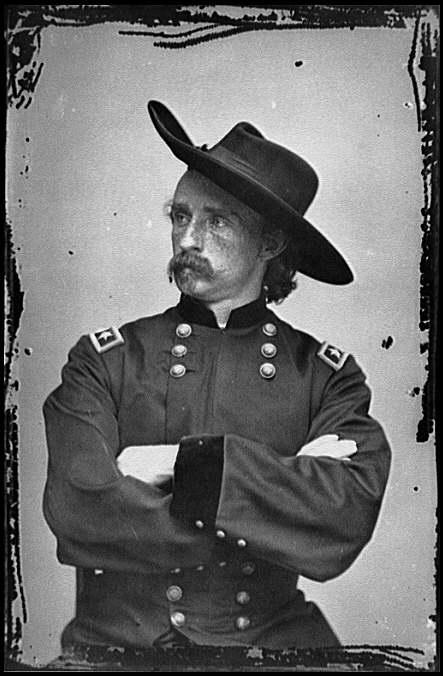

Indoors, an emphysemic historian with liquid sibilants lectures a seated assemblage on the nature of The Battle. Through his words, all but a few whose patience and vocabulary are limited by childhood see the outcome’s inevitability. He is generous to Custer’s memory with his invocation of Murphy’s Law as a causal force. But the main wall is Custerolatry: movie posters and books, some of them published when 7th Cavalry widows were still in black, that praise the bravery instead of the folly.

It is always thus. Soldiers die. And we overlook the errors of judgment (and sometimes demonize those who point them out) so that we can say that our men and women did not die in vain. But sadly, soldiers often march obediently and with great, blind loyalty into the valley of death, led by fools or villains. It is a patriot’s job to expose such folly or villainy.

It is always thus. Soldiers die. And we overlook the errors of judgment (and sometimes demonize those who point them out) so that we can say that our men and women did not die in vain. But sadly, soldiers often march obediently and with great, blind loyalty into the valley of death, led by fools or villains. It is a patriot’s job to expose such folly or villainy.

It may take years, but attitudes can change. A metallic memorial, its letters acetylene-raised, handmade welts, sits prominently, if informally, in the museum building, remembering the Indians who died, anonymous because their bodies were not left for the sun, the dogs, the vultures, and the hagiographers. And note the focus of the only paragraph on the National Park Service’s Little Big Horn Battlefield home page:

This area memorializes one of the last armed efforts of the Northern Plains Indians to preserve their way of life. Here in 1876, 263 soldiers and attached personnel of the U.S. Army, including Lt. Col. George A. Custer, met death at the hands of several thousand Lakota and Cheyenne warriors.

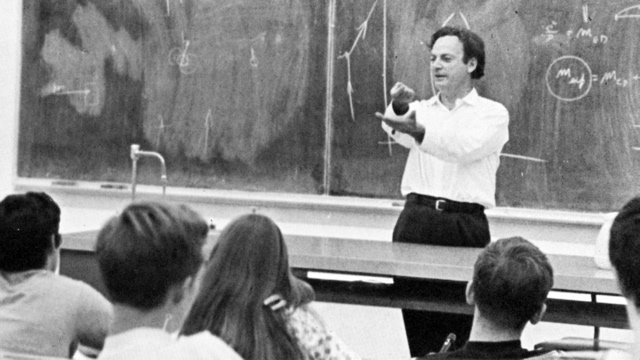

When Richard Feynman came back to Ojai’s Summer Science Program in 1960 for a second, unscheduled visit, his topic was what he called “smallness.” Today that field, in which he was a visionary, is called nanotechnology.

When Richard Feynman came back to Ojai’s Summer Science Program in 1960 for a second, unscheduled visit, his topic was what he called “smallness.” Today that field, in which he was a visionary, is called nanotechnology.

In 1960, I sat on the floor, leaning against the wall, my feet thrust out, listening to Caltech’s

In 1960, I sat on the floor, leaning against the wall, my feet thrust out, listening to Caltech’s  My mother died ten years ago this week, and I am brought to think of the vanishing point, that not-so-distant past beyond which none of us can know the fathers and mothers who brought us here.

My mother died ten years ago this week, and I am brought to think of the vanishing point, that not-so-distant past beyond which none of us can know the fathers and mothers who brought us here. What actually happens is not always in the history books.

What actually happens is not always in the history books. Almost two months had passed by my Harvard freshman door. It was 1961, early November, and the air was crisp and blue-gray. I had moved into

Almost two months had passed by my Harvard freshman door. It was 1961, early November, and the air was crisp and blue-gray. I had moved into  The day is overcast, cold, and wet. Forty-eight degrees feels colder in this Great Plains wind. A National Parks ranger gives a spirited description of tactics and weaponry. He almost prances as he gestures across the swales of brown grass, sweeping his hands from side to side to indicate how the advancing Sioux were able to slip from dip to dip without being seen.

The day is overcast, cold, and wet. Forty-eight degrees feels colder in this Great Plains wind. A National Parks ranger gives a spirited description of tactics and weaponry. He almost prances as he gestures across the swales of brown grass, sweeping his hands from side to side to indicate how the advancing Sioux were able to slip from dip to dip without being seen.