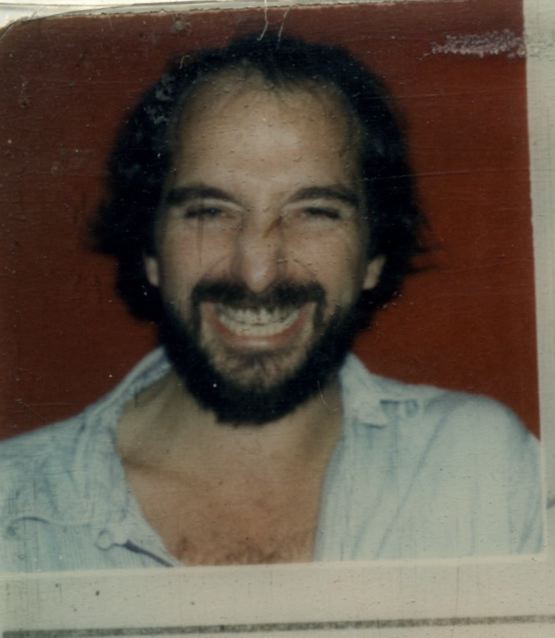

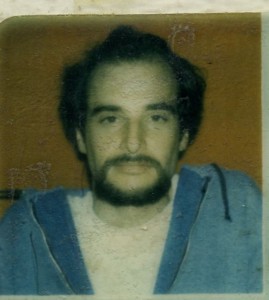

On a balmy Saturday morning in late-1978, two 30-something brothers boarded a Pacific Southwest Airlines flight in Los Angeles. As they walked up the outdoor stairway into the PSA jet, the two men looked suspiciously like Arab terrorists during a time when Arab terrorism was non-existent. They were traveling under their real names, but to almost any observer they could have been Ali Balak Qatlar and Satif Luwi Qatlar. The former looked deranged, the latter somewhat simple.

On a balmy Saturday morning in late-1978, two 30-something brothers boarded a Pacific Southwest Airlines flight in Los Angeles. As they walked up the outdoor stairway into the PSA jet, the two men looked suspiciously like Arab terrorists during a time when Arab terrorism was non-existent. They were traveling under their real names, but to almost any observer they could have been Ali Balak Qatlar and Satif Luwi Qatlar. The former looked deranged, the latter somewhat simple.

Their destination was Oakland, where they would be met by their widowed 61-year old mother. She had decided to move from the East Bay to Los Angeles to be closer to her sons and had requested their packing and moving help.

They referred to themselves as screenwriters, work that had not yet brought in any significant rewards. Being a screenwriter with little income was commonplace in Los Angeles. Satif, a Harvard Business School MBA, had done a not-so-unscientific survey the previous year that indicated upwards of 30,000 screenplays were always available for purchase in the area surrounding the studios (from Hollywood west to the ocean plus the San Fernando Valley). Almost every dentist, massage therapist, and waiter had something on a shelf.

They referred to themselves as screenwriters, work that had not yet brought in any significant rewards. Being a screenwriter with little income was commonplace in Los Angeles. Satif, a Harvard Business School MBA, had done a not-so-unscientific survey the previous year that indicated upwards of 30,000 screenplays were always available for purchase in the area surrounding the studios (from Hollywood west to the ocean plus the San Fernando Valley). Almost every dentist, massage therapist, and waiter had something on a shelf.

Success was elusive, but occasionally someone won, so the brothers worked hard…and constantly.

It was a full flight. The only two seats together were in the back…the last row. The brothers sat, buckled up, and watched out the window as the plane lifted up over the Pacific Ocean and turned northward. A few minutes later the stewardess (this was the era before “flight attendants”) offered orange juice and coffee in paper cups. The men accepted, drank, and drew no attention to themselves.

It was a full flight. The only two seats together were in the back…the last row. The brothers sat, buckled up, and watched out the window as the plane lifted up over the Pacific Ocean and turned northward. A few minutes later the stewardess (this was the era before “flight attendants”) offered orange juice and coffee in paper cups. The men accepted, drank, and drew no attention to themselves.

Refreshments consumed, Ali turned to Satif. “Okay, here’s your stay-sharp writing assignment. We’re going to come up with a scene.”

It was here that Ali unwittingly set the brotherly caravan on an unstoppable rendezvous with disaster. “Let’s say that you’re a hijacker,” he began, “and I’m your prisoner. Somehow I have to let the pilot know that the plane is in danger. How do we write the scene?”

Satif gave a weary sigh, “I’m tired. I think I’ll nap.” Sitting in the window seat, he rested his head against the fuselage wall and closed his eyes. About an hour later, he awoke to the seatbacks-and-traytables announcement. The stewardesses picked up the empty cups, and the BAe-146 Smiliner descended over San Francisco Bay, landing on time in Oakland, and taxied to the gate.

Satif gave a weary sigh, “I’m tired. I think I’ll nap.” Sitting in the window seat, he rested his head against the fuselage wall and closed his eyes. About an hour later, he awoke to the seatbacks-and-traytables announcement. The stewardesses picked up the empty cups, and the BAe-146 Smiliner descended over San Francisco Bay, landing on time in Oakland, and taxied to the gate.

The two men were the last to reach the exit door. As Satif looked out past Ali, he noticed, but did not react to, two men in dark suits standing on the ground, each about five yards from either side of the roll-to-the-plane stairway, hand inside suit jacket. One step later, just as Satif’s foot  touched the stairs’ top platform, both his arms were grasped by men identically besuited.

touched the stairs’ top platform, both his arms were grasped by men identically besuited.

“Would you come with us, sir?” one of the men said. It was not really a question.

“What’s the problem?” Ali asked.

“Please come with us, too.” the other man-in-black said firmly.

Satif and Ali were led across the tarmac to a nondescript room where they were searched and interrogated. (When asked today about their ordeal, both agree that it was fortunate that their questioning took place one month before Dick Cheney was elected to represent Wyoming in the U.S. House of Representatives.)

It took an hour for Satif and Ali to convince the Federal officers that their government-issued driver licenses (same last name, same home address) demonstrated that they were brothers, and that it was unreasonable to assume that one of them was holding the other hostage.

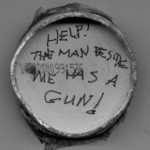

It was then that one of the gendarmes produced the artifact that triggered the bust: a paper cup.

It was then that one of the gendarmes produced the artifact that triggered the bust: a paper cup.

Ali gasped and, in a flood of explanation, revealed all.

“It was a movie scene. I mean, I asked my brother to— But he was asleep.”

After explaining the setup (hijacker and hostage), Ali continued, “The scene needed for my character to get a message to the pilot without the hijacker noticing. How do you do that? And then, while I was finishing my coffee, I figured it out.”

Ali got animated, waving his arms like a film director mapping out a take for his crew. “You film the actor draining his cup, but then, instead of setting it back on the tray, he drops his hand into his lap, and with the other hand, takes his pen and upside-down, without looking, he writes a message on the bottom of the cup. We lift the row of seats into the air and shoot straight up, right between his legs, zooming in so we can actually read the message as he writes it.”

Satif saw the main interrogator’s mouth twitch upward slightly.

“But my brother slept the whole flight, and by the time we started down, I had completely forgotten about it.” He paused. “But…since you guys are here, I guess the scene works.”

The G-men kept us for another 30 minutes, one of them pitching a “terrific idea for a movie,” while Mom watched our baggage rotate.

5 Comments on “Sheiks on a Plane”

Oh my goodness… Look at all your hair!

Is that the actual cup?

No interviews will be granted.

those are now stock images when you google search for “arab terrorists”

OMG! I hope Homeland Security finds those guys…because I’d like to look that good again!

Comments are closed.