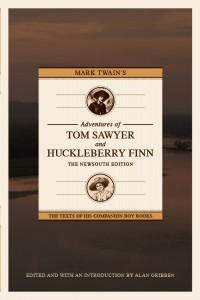

Recently, NewSouth Books announced the publication of a new version of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. Bowdlerized by Auburn University’s Dr. Alan Gribben, Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, is described by NewSouth thusly:

Recently, NewSouth Books announced the publication of a new version of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. Bowdlerized by Auburn University’s Dr. Alan Gribben, Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, is described by NewSouth thusly:

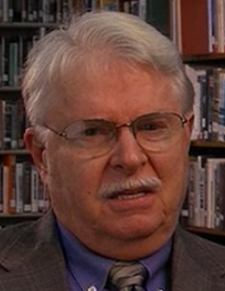

In a radical departure from standard editions, Twain’s most famous novels are published here as the continuous narrative that the author originally envisioned. More controversial will be the decision by the editor, noted Mark Twain scholar Alan Gribben, to eliminate the pejorative racial labels that Twain employed in his effort to write realistically about social attitudes of the 1840s.

Not surprisingly, Professor Gribben’s decision to replace the word nigger with slave has engendered controversy.

Leonard Pitts, Jr., a Miami Herald syndicated columnist, addressed this revision of Twain’s masterwork in his January 9, 2010, column.

[I]t is troubling to think the state of reading comprehension in this country has become this wretched, that we have tweeted, PlayStationed and Fox Newsed so much of our intellectual capacity away that not only can our children not divine the nuances of a masterpiece, but that we will now protect them from having to even try.

Dumbing down…ever dumbing down. This is a sad testament to the state of American education.

* * * * *

Here is Pitts’ column in its entirety.

It is, perhaps, the seminal moment in American literature.

Young Huck Finn, trying to get right with God and save his soul from a forever of fire, sits there with the freshly written note in hand. “Miss Watson,” it says, “your runaway nigger Jim is down here two mile below Pikesville and Mr. Phelps has got him and he will give him up for the reward if you send.”

Young Huck Finn, trying to get right with God and save his soul from a forever of fire, sits there with the freshly written note in hand. “Miss Watson,” it says, “your runaway nigger Jim is down here two mile below Pikesville and Mr. Phelps has got him and he will give him up for the reward if you send.”

Huck knows it is a sin to steal and he is whipped by guilt for the role he has played in helping the slave Jim steal himself from a poor old woman who never did Huck any harm. But see, Jim has become Huck’s friend, has sacrificed for him, worried about him, laughed and sung with him, depended upon him. So what, really, is the right thing to do?

“I was a-trembling,” says Huck, “because I’d got to decide, forever, betwixt two things and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:

‘All right, then, I’ll go to hell’ — and tore it up.”

When NewSouth Books releases its new version of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn next month, that revelatory moment will contain one troubling change. Publisher’s Weekly reported last week that in this edition, edited by Twain scholar Alan Gribben of Auburn University, all 219 occurrences of the so-called N-word will be cut. Huck’s note will now call Jim a “runaway slave.” Twain’s use of the word “Injun” will also be struck.

Gribben brings good intentions to this act of literary graffiti, this attempt to impose political correctness upon the most politically incorrect of American authors. He told PW that many teachers feel they can’t use the book in their classrooms because children simply cannot get past that incendiary word. “My daughter,” he said, “went to a magnet school and one of her best friends was an African-American girl. She loathed the book, could barely read it.”

But while Gribben’s intentions are good, his fix is profoundly wrong. There are several reasons why.

In the first place, any work of art represents a series of conscious choices on the part of the artist — what color to paint, what note to play, what word to use — in that artist’s attempt to share what is in his or her soul. The audience is free to accept or reject those choices; it is emphatically not free to substitute its own.

In the second place, it is never a good idea to sugarcoat the past. The past is what it is, immutable and non-negotiable. Even a cursory glance at the historical record will show that Twain’s use of the reprehensible word was an accurate reflection of that era.

So it would be more useful to have any new edition offer students context and challenge them to ask hard questions: Why did Twain choose that word? What kind of country must this have been that it was so ubiquitous? How hardy is the weed of self-loathing that many black people rationalize and justify its use, even now?

So it would be more useful to have any new edition offer students context and challenge them to ask hard questions: Why did Twain choose that word? What kind of country must this have been that it was so ubiquitous? How hardy is the weed of self-loathing that many black people rationalize and justify its use, even now?

I mean, has the black girl Gribben mentions never heard of Chris Rock or Snoop Dogg?

Finally, and in the third place, it is troubling to think the state of reading comprehension in this country has become this wretched, that we have tweeted, PlayStationed and Fox Newsed so much of our intellectual capacity away that not only can our children not divine the nuances of a masterpiece, but that we will now protect them from having to even try.

Huck Finn is a funny, subversive story about a runaway white boy who comes to locate the humanity in a runaway black man and, in the process, vindicates his own. It has always, until now, been regarded as a timeless tale.

Huck Finn is a funny, subversive story about a runaway white boy who comes to locate the humanity in a runaway black man and, in the process, vindicates his own. It has always, until now, been regarded as a timeless tale.

But that was before America became an intellectual backwater that would deem it necessary to censor its most celebrated author.

The one consolation is that somewhere, Mark Twain is laughing his head off.

One Comment on “Mark Twain and the N-word”

When I had literarily inclined friends preview my book, “The Sipsey Swamp Stories,” some of them objected to several potentially derogatory words I had used in my story that is set in over-fifty-years-ago Alabama. One reviewer said that “Negro” should be replaced with “African American.” Most surprising to me, I was told that “sissy” should not be used.

According to the reviewer, sissy has gone from being a childhood taunt to a heavily freighted sexual classification.

Since my book was aimed primarily at children, I removed or changed most of the possible offenses, but I think that an author writing about times long past should use the language of that time and place. In no case should a well-known author’s words be butchered.

But what do I know? Just call me a nincompoop.

Comments are closed.